What can’t we just create

At 3 p.m. on Tuesday 21 December, a new site-specific art project, “what can’t we just create” by Kristaps Ancāns, will be opened on 2 Nikolaja Street, Daugavpils Fortress.

Curator: Corina L. Apostol

Before anything, the Latvian-British artist Kristaps Ancāns considers himself an explorer. Fuelled by the necessity to visualise and communicate as directly as possible, he plays with the hidden mechanisms behind linguistic, cultural and contextual systems that define us. Through metaphorical and philosophical questions, quizzical puns and statements, Ancāns has developed a practice in site-specific installations, employing large-scale banners that immediately engage with the public. Based on topical issues culled from media and literature, and stories from his own cultural heritage and identity, the artist charts dynamic and unexpected relationships between language, context and image.

In what can’t we just create (2021–2022) – the artist’s first large-scale project for the Rothko Centre – Ancāns’ practice has grown both formally and conceptually. The project combines monumental banners with a site-specific sculpture: texts in black font on a white background (written in Latvian, Russian and English), colour photography and a lone palm tree. Located on and around a disused building that once housed former air pilots and war machinery, the piece addresses the city and population of Daugavpils directly – its histories of perpetual war-readiness and traumas from national self-determination, including those who still live among the vestiges of the past, in an area that’s developing quickly. Ancāns’ project in the former military fortress refers to constructions and confluences of language and context mechanisms inherited by and inherent of the site that is actively transforming into a vibrant cultural hub and administrative centre for the region.

The wordplay in the aforementioned languages (“what can’t we just create / can’t we just create / we just create / just create”) – which ends on the negative form in Latvian (“nevaram uztaisīt”), and on the positive in Russian and English (“можем сделать” / “just create”) – functions as a “thinking image,” summoning concepts of otherness and of exhaustion towards their uncharted potentialities. On the banner, they are linked in a suggested yet unresolved symmetry. Who are the insiders? And who are those doomed to the periphery, somewhere other than the centre? The wordplay leaves us in a knotty paradox. As viewers, we are caught in the conundrum of remaining as outsiders, though equally joining the centre, as a consequence of being ex-Eastern Europeans in a former communist country (even though Latvia joined the EU in 2004). For the Russian-speaking population of the country, the otherness of living in a double periphery of the EU is even more acutely complex.

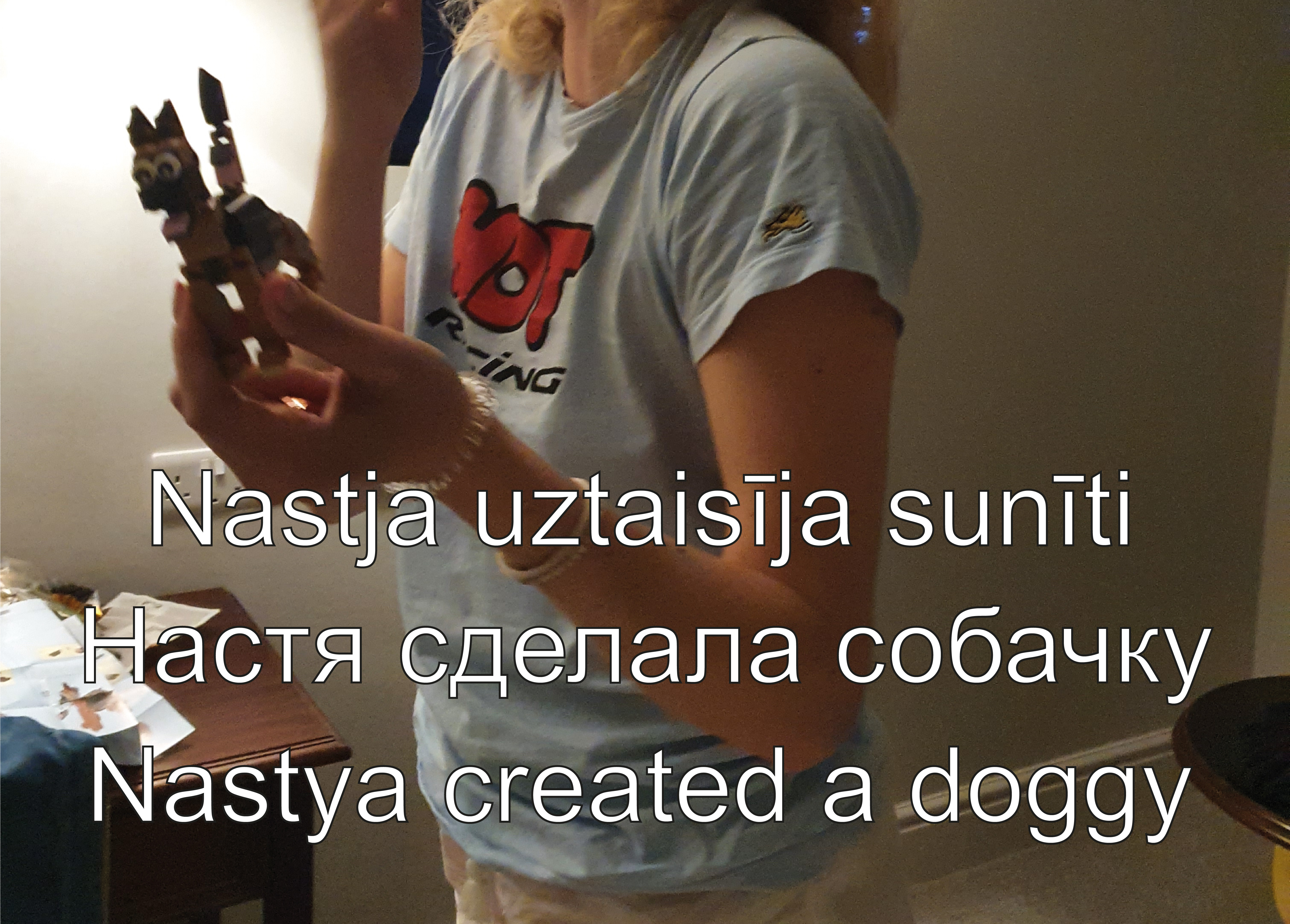

Adjacent to the banner with text, the viewer encounters another tripartite: a brightly lit portrait of a young woman, who’s smiling while holding a miniature toy dog, is captioned with “Nastya created a doggy” (short for “Anastasiya” in Russian) in the translated languages. The large-scale portrait plunges the viewer into contemplation. And through a gesture of playfulness, its inclusion stirs them to consider how the sense of otherness and sensations of fatigue, evoked by each corresponding banner, can be paradoxically flipped on its head. The portrait brings a carefully staged levity and spontaneity to the building’s austere façade – its exterior engulfed in green mesh, melded with the rich emerald setting and deep red on Nastya’s t-shirt, which provocatively reads “Hot Racing”.

Altogether, these banners visualise the nexus of identity, language and geography – from integration to otherness, verbal to nonverbal, corporeal to immaterial, tone to shade. At this time in history, they offer a glimpse of the shape, complexity and “colour” of the context and affect they surround. Such witty ambiguities are key to the artist’s repertoire; transforming the site into a ludic realm of self-conscious laughter, viewers can only reflect on the realities that are portrayed, contributing to their own sense of questioning, discomfort and awe.

The textual patterns that reveal the conundrums of context and identity construction suggest connections between the artist’s work and “Concrete Poetry,” which emphasises visual and auditory content, and the form of language. Taken together, aspects of the otherwise straightforward banners underscore the specific, namely each viewer’s particular relation to the exotic, or otherness, linking its specificity with the more common idea of creating, and therefore, coexisting. Ancāns uses humour to level emergent circumstances of conflict and alienation, undermining difference (exoticism) and foregrounding commonality (creation), instead.

In direct dialogue with the visual onslaught of the conditions of identity and sources of knowledge that entangle (inter)national narratives through language, the artist has created a sculpture of a resting palm tree (made of aspen wood) nestled between two linden trees that stand on-site. The sculpture sets the stage for the installation in its entirety – the wavy trunk of the palm climbing upward, pointing toward the walls where the banners hang. Open to the public during the darkest and coldest time of the year in Latvia, the sculpture playfully contrasts with the bare trees, the dead foliage and the scattered snow all littered on-site. In this expanse, the artist knows to fill and balance aesthetic information; to play with different scales, visual references and languages, translating the complexities of social behaviour into art.

While linden and aspen trees are native to the region (which may evoke a common sensation of familiarity), the palm’s sculptural form signifies exoticism, invoking individualistic notions of how another person might be considered “different.” At the University of Latvia’s Botanical Garden, palm trees are indeed a prized possession; as one of its main attractions, the Palm House conjures the warmth of the tropics in the depths of Baltic winters. In this context, the palm is a signifier of human inconsistency, of anomaly and desire, and of loneliness in a foreign land. Its marked artificiality – rooted in local material, nonetheless – speaks of the incongruity of national/regional ideologies, the absurdity of strangeness and the difficulty of coming to terms with the Other.

what can’t we just create (2021–2022) unifies disparate ideas and concepts. Combining words and images, plays on language, ambiguity and displacement, the site-specific installation raises questions on the inelegant and alienated manners of relating to other human beings supplementary to ourselves. Ancāns juxtaposes seemingly dissimilar elements that both surprise and humour our expectations and beliefs in identities and heritage. And we laugh nervously, recognising that we – collectively – face these difficult and complicated questions together.

Author:

British-Latvian artist Kristaps Ancāns focuses his practice on investigating the confusion between humans, nature and machines through a conceptual game with its own artificial intelligence. He works across media in the fields of sculpture, text and installation that often contain a kinetic component. Ancāns has exhibited, lectured and taught internationally, including such venues as Publiek Park/S.M.A.K Museum, The Latvian National Opera and Ballet, Rīga International Biennale of Contemporary Art, Careva Contemporary, Code Art Fair Copenhagen, Domobaal Gallery, Tate Exchange/Tate Modern, Museum of London, Royal Academy of Arts London, PEER, Vienna Contemporary, Tallinn Art Hall, Setouchi Triennale and Tokyo University of the Arts. He holds an MFA from Central Saint Martins, with distinction, and has been awarded the Cecil Lewis Sculpture Scholarship and the Helen Scott Lidgett Award. Currently, he is the Head of the Master of Contemporary Art Programme at the Estonian Academy of Arts and the Head of POST, an interdisciplinary MA Programme at the Art Academy of Latvia. The artist lives and works between London, Rīga and Tallinn.

https://www.kristapsancans.com/

Curator:

Corina L. Apostol is a curator at the Tallinn Art Hall and the curator of the Estonian Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale. She curated the Shelter Festival: Cosmopolitics, Comradeship, and the Commons at the Space for Free Arts in Helsinki (2019). She was the Mellon Fellow at Creative Time, where she co-edited “Making Another World Possible: 10 Creative Time Summits, 10 Global Issues, 100 Art Projects” and co-curated the Creative Time Summit “On Archipelagoes and Other Imaginaries” (2018) in Miami. Apostol obtained her Ph.D. at Rutgers University, where she was also the Dodge Curatorial Fellow at the Zimmerli Art Museum. She is the co-founder of ArtLeaks and editor-in-chief of the ArtLeaks Gazette. She has been longlisted for the Kandinsky Prize (2016) and the Sergey Kuryokhin Prize (2020) and has won the apexart 2022–2023 exhibition proposals competition (NYC).

Image: Kristaps Ancāns, what can’t we just create (detail) 2021/2022, site-specific installation