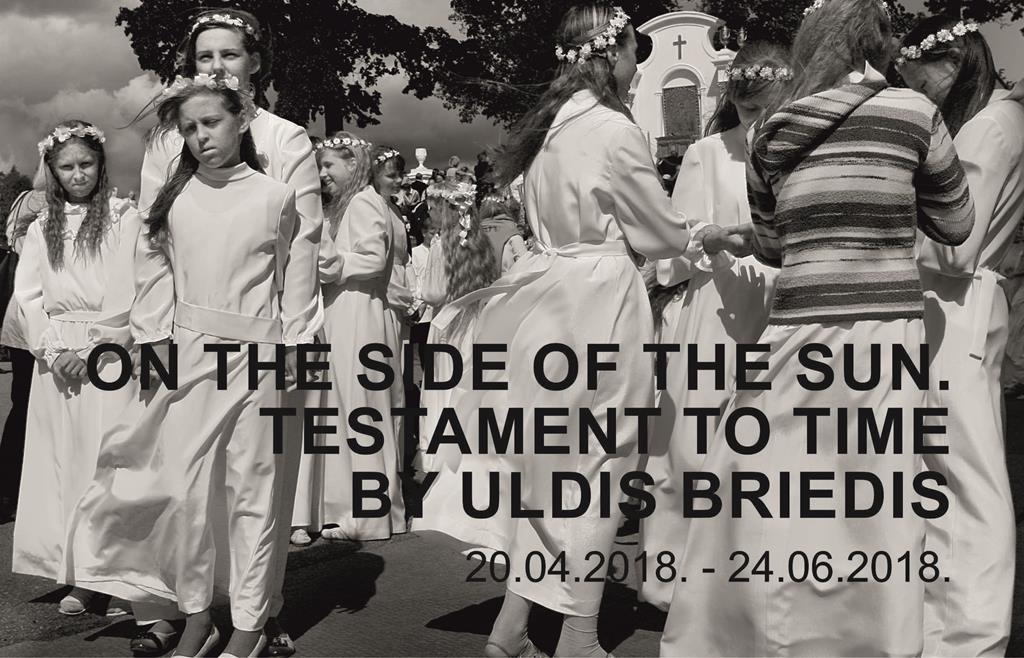

On the Side of the Sun. Testament to Time by Uldis Briedis

The essence of Uldis Briedis’ photographic archive is measured in time and not size. His path as a documentarian has crossed several time zones – the Soviet period, the National Awakening, the chaos of the 1990s, our current time and something else rather unfathomable to the mind – which I’d like to refer to as congealed time in Siberia. The exhibition at Daugavpils Mark Rothko Centre is going to be the largest show of Uldis Briedis’ work to date, and will feature, as a testimony to time, a significant number of images gathered over 50 years.

Documentary photography records occurrences and outlines the face of time without the photographer noticing. Portraits make up a large portion of Uldis Briedis’ work, stemming directly from his job as a photo journalist for several newspapers – initially in Liepāja (in the 1960s-70s) and later in Riga for Padomju Jaunatne [Soviet Youth] and Diena [Day]. People in his photos are depicted in ordinary settings and positions, thus allowing their surroundings to contribute to the photographer’s desire to look further, more searchingly and deeper than the actual task requires. Information contained in his photos enriches the registers stored in our collective consciousness that are necessary for cultural historical referencing and emotional understanding. Moreover, it accomplishes this task better than many a tale recorded as oral history, since Uldis Briedis’ reputation as a documentary photographer doesn’t remotely suffer from the most prevalent disease of our times of misrepresenting, supressing and manipulating facts and images. He operates like a hunter with a camera: he waits until the right moment arrives or, on the contrary, the shot rather fortuitously and unexpectedly pops up in front of him. His approach is simple: “You must look around in a 360-degree range, it’s impossible to prepare in advance, you must be quick and ready to make use of every situation presented to you by life. You can’t invent it. My own character suits this approach and so it seems somewhat self-explanatory to me that I became a reporter.” However, in Uldis Briedis’ case his documentary photography or photojournalism is personal and clearly conveys his attitude. His photographs of politics and politicians are critical and kind-heartedly or ironically mocking. There are several close-ups of the militsiya (Soviet police) taken during the Soviet period, which ended in the photographer being arrested. Gradually and consistently he began to photograph the militsiya and Soviet armed forces from behind, as if they had casually turned around to leave.

His personal attitude and sentience emanates from every theme that becomes the focus of Uldis Briedis’ attention. Take the seascape for instance – his first passion as a photographer and reporter after a five-year long career as a mariner. He shot his first seascape during a heavy storm after wading in far beyond the second sandbank. Afterwards viewers often asked him: “Did you take a photo of a painting?” He portrays his friends and contemporaries with a natural ease and seemingly effortlessly – fishermen and bohemians in Liepāja, intellectuals and workers, creating characters that represent certain values and shape the history of Latvia along with the The destruction of traditional farmsteads in the Latvian countryside and the portraits of the people guarding the barricades in 1991. Some of the most powerful work in this exhibition are photographs from his legendary bicycle trip to Siberia in 1975 together with Ingvars Leitis. As a compelling visual story, these images reflect the tragic reality of mid-20th century life of the descendants of Latvian settlers who had arrived there in the late 19th century.

While looking at Uldis Briedis’ photographs, I am fascinated by the thought that a photograph taken as illustrative material for a newspaper article can live an independent life regardless of context and remains interesting to an unlimited number of viewers because of the author’s strength of personality, attitude, thoughts and emotions. The essence of time resides in these photographs and is always contemporary.

Text: Aiga Dzalbe

Curator Inga Brūvere, in collaboration with Aiga Dzalbe

Uldis Briedis (1940) is well-known as a long-time photographer for the newspaper Diena. During the Soviet period he worked as a photojournalist for the newspaper Padomju Jaunatne, as well as the Liepāja newspapers Komunists and Ļeņina Ceļš. Over almost fifty years of active work as a photographer his work has been published countless times in many press publications. On several occasions he was arrested while carrying out his work. Uldis Briedis’ name is closely associated with the most significant achievements of photojournalism in Latvia in the second half of the 20th century. He has received several awards, more than once has been recognised as Best Press Photographer (1984 and 1988), and was awarded the Prize of the Latvian Journalists’ Union (1988). In 2010, Neputns publishing house released the book Time Hunter, dedicated to the artist and compiled by Laima Slava. In 2011, he was awarded the Order of the Three Stars.