The recent paintings of Jon Arne Mogstad: Looking into the contemporary sublime?

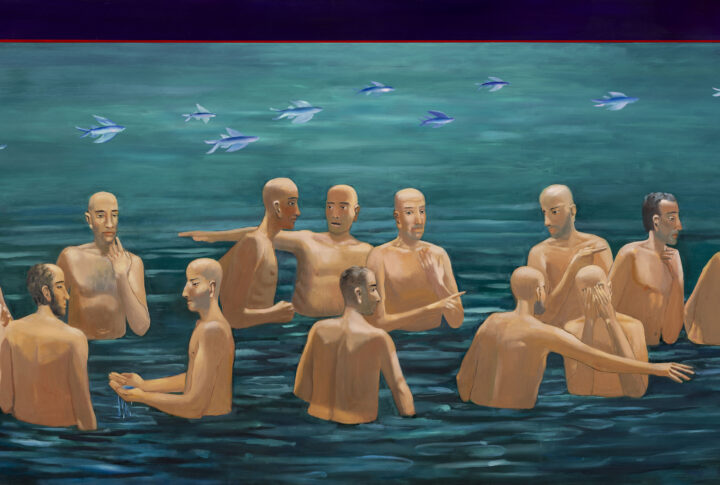

The notion ‘dialogue’ could be interpreted as something that is open, never ending, unfinalized. According to Mikhail Bakhtin, “… there is neither a first nor a last word, and there are no limits to the dialogic context (it extends into the boundless past and the boundless future)”.1 In his three recent series of paintings, Mogstad sets out to explore the pictorial space, referring to art history, time and presence. He offers a dialogue in which to find traces of his own art since the 80s, the history of art from Early Renaissance via Baroque and Romanticism to Dadaism, Hard Edge paintings and Abstract Expressionism. Mogstad is investigating different angles and perspectives, and a plethora of pictorial languages from the more figurative to the more abstract ones. In addition to referring to the history of art, his paintings even relate to music, literature, poems, film, and popular culture.

There are of course different perspectives. It is possible to interpret the paintings as balancing a certain tension between the beautiful and the sublime, two aesthetic categories tending to be looked upon through history as complete opposites. Both the beautiful and the sublime are ambiguous as historical concepts, in art history, aesthetics and philosophy, spanning from antiquity to the present. According to Philip Shaw, the sublime has stood for “the effect of grandeur in speech and poetry … for the contrast between the limitations of human perception and the overwhelming majesty of nature; … as a signifier for that which exceeds the grasp of reason …”2 To mention some. In the short essay, “The Sublime is Now!” (1948)3, Barnett Newman relates the sublime to presence, to a now, a here, a sense of beyond. What then, is the ‘sense of beyond’? In the words of Shaw, it is nothing other than an effect of oil on canvas.4 The sublime has to do with a creative intensity, a certain attentiveness towards our own time. For Harold Rosenblum, the notion of the sublime could be related to Abstract Expressionism just as well as to Romantic landscape paintings, due to the atmosphere, and the immensity and vastness of those paintings.5 The term ‘contemporary sublime’ is borrowed from Simon Morley, who discusses the concept of the sublime through history, and suggests an interpretation of the contemporary sublime as an immanent transcendence.6

Some writers have related the paintings of Mogstad to the notion of the sublime in one or other way, both because of the intensive light, the immense depths (relating to Romanticism and Romantic landscape paintings), and because of the dimensions of the paintings. The series of paintings Mogstad created in 2015, Music of Chance, consists of intense, organic, flowing colour fields, originating from both chance and controlled procedures: textile colours being poured on the large canvases, where they trickle and flow, and blend. Still, it is not entirely chance; Mogstad chooses the colours, and the direction they would take on the canvas. In his work, one finds a method based on improvisation, embodied in an intimate knowledge of the medium, knowledge about the physical paint itself, and the history of painting through the ages, and chance procedures and techniques are thus allowing something unexpected to happen in the paintings.

The series Music of Chance is reminding us of the somehow painterly sublime as seen in Romanticism and Romantic landscape paintings. Music of Chance carries traces and reminders of art history, such as the variety of studies of the changing sky made by artists like J.M.W. Turner, or motives like rough seas or volcanic eruptions frequently found in the paintings by C.D. Friedrich or J.C. Dahl. Even the gestures or the vastness of American post-war paintings is to be found (Rothko, Newman, Pollock, Frankenthaler, Clyfford Still, and more). Perhaps one even could trace a reference to the drawings of Joseph Beuys.

The 2016 series Veils contains a quiet, and secretive beauty, vaguely reminding us of paintings from the earliest Renaissance, as well as the more recent, modern history of art. In this series, Mogstad has painted layers of white on white, exploring the different aspects of whiteness forming grids. He has used both textile colours and the tender and beautiful early colour pigments like the ones used by artists in the Early Renaissance (Malachite, Lapis Lazuli, Naples Yellow, and more). The result, what we see in the paintings, is layers upon layers, something is hidden, something is disclosed; like a palimpsest: There are depths and geometrical forms, grids, there are references to early art history as well as emblematic Modernism, musicality and atmosphere, traces of earlier paintings, even traces of the series Music of Chance.

According to Bakhtin, “… time thickens… takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time … and history…”7 Could we look upon the work of Mogstad as a wandering through, and a dialogue with, almost the entire history of art? In the three recent series of paintings, taking three different steps exploring the medium, Mogstad asks the question time and time again: What could a painting be, today?

Hege Charlotte Faber, December 2017

- Mikhail Bakhtin, “Toward a Methodology for the Human Sciences,” in Speech Genres and Other Late Essays, ed. Michael Holquist and Caryl Emerson (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1986 ), 170.

- Philip Shaw, The Sublime (London: Routledge, 2006), 4.

- Barnett Newman, “The Sublime Is Now,” in Art in Theory, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992 [1948]).

- Shaw, The Sublime, 7.

- Robert Rosenblum, “The Abstract Sublime,” in New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970, ed. Henry Geldzahler (New York: Dutton, 1969).

- Simon Morley, “Staring into the Contemporary Abyss,” Tate Etc no. 20 (2010).

- Mikhail Bakhtin, “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel,” in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981 [1937–1938]), 85.