DŽEMMA SKULME SUBSTANCE AND FORM. PATHOS AND RESIGNATION.

DŽEMMA SKULME

SUBSTANCE AND FORM. PATHOS AND RESIGNATION.

How does an artist act? Džemma Skulme slightly opens the door to her creative kitchen: “For example, while painting you have a feeling that you fail, fail and will never succeed. But you also know that there will be a moment and you will succeed. As if some forces come to help you to cope with everything. (..) And this is not what you call the inspiration, because at that moment you feel absolutely drained. And just because you feel totally drained you still continue, – something helps you, and then you succeed, the result is even better, and you celebrate victory. These are the deepest, the most

secret, inexplicable creative feelings.”1

What kind of victory does an artist celebrate after she has felt utterly “drained”? What is it that transforms an everyday weakness and resignation into a great emotional uplift and pathos of creation? Is this victory the truth about which one of the most captivating interpreters of art metaphysics, Martin Heidegger, so solemnly speaks, ascribing to the nature of truth the ability to break outside and the tendency to posit itself into the art work? Is this victory the creation of what has been experienced – “waiting and receiving in the relationships with non-secrecy” 2

Or – the argument you have gone through during the process of truth and which breaks out when the debaters face each other – lighting up and secrecy, because the truth is “untruth ”, as Heidegger writes, and “the sphere of the appearance of the yet-undiscovered in the sense of secrecy belongs to it”? But perhaps victory is an image, which has emerged during the abstract argument between lighting up and secrecy, embodying into a substance – in the glow of colors, in virtual stages of text collages, picturesque masses, which “in their movement obtain strange strokes”3

This solo exhibition of Džemma Skulme’s works is arranged so that all art works together would not only form a competently arranged “art life”, but at each of its point some question would also arise, and there would be something unknown encouraging to think about the complicated procedure of creating. This was initiated by both a wish to arrange a different exhibition in honor of a prominent, charismatic artist, a brilliant leader of art life4 and a splendid leader on the political stage of the Awakening period, Džemma Skulme, and also by the truth that “Džemma Skulme has always been among the recognized, but seldom, very seldom, has been understood” 5.

When in the 50-s Džemma Skulme became known in art world and also later when her style was ripening, the political status of art and its ideological function were one of the major problems, as we would say it today. Formally,

art belonged to people, but everything that belonged to people belonged to the party or the power. De facto art lived like a double agent – it collaborated with institutions and received belligerent commissioned orders whose rhetorical aim a priori was a total victory of socialism. But

in the studio art lived for art’s sake, studied and created the constructive elements of form outside the ideological space – abstractly, and also freely loved art of the whole world and of all times. It seems that just the recent dangerous transformations in a public space, which have

aroused Europe from a lazy liberalism, help to understand what fear, threats and nonviolent resistance actually mean.

The problem which today’s Latvia faces is the fact that the official purchases made in the Soviet time still have a political status. Passively, but still. This automatically projects onto the authors of art. And an intelligent deconstruction of this status is a challenge with which

the contemporary situation does not cope very well. There is lack of time, money and strategy. During these two decades something has been done to correct the Soviet history (known to a wider public – the exhibition “…and other trends, searches, artists in Latvia 1960 – 1984”, 2010, integrating design and kinetics; the exhibition “Movement. Visvaldis Zariņš”, 2012, inscribing in history the name unknown until then). However, the present situation shows that the most difficult thing is not the discovering of those who have been forgotten and ignored by the power, but rather the disentangling from the oppression of power of those “counted” to it.6

We must know not only how to criticize and mythologize the Soviet art, but also how to protect and incorporate art works of that time into the contemporary culture. What has been created cannot become existent, unless there is somebody to protect it. Artists, whose assistance the power used to write its history, have not met with purposeful purchases in modern times so that their personal time, their outstanding works of the Soviet time could get into museum collections. After having been criticized at solo exhibitions or even having not been accepted for the exhibitions, these works pile up on the studio shelves.

THE OFFICIAL, DOUBTFUL AND UNOFFICIAL

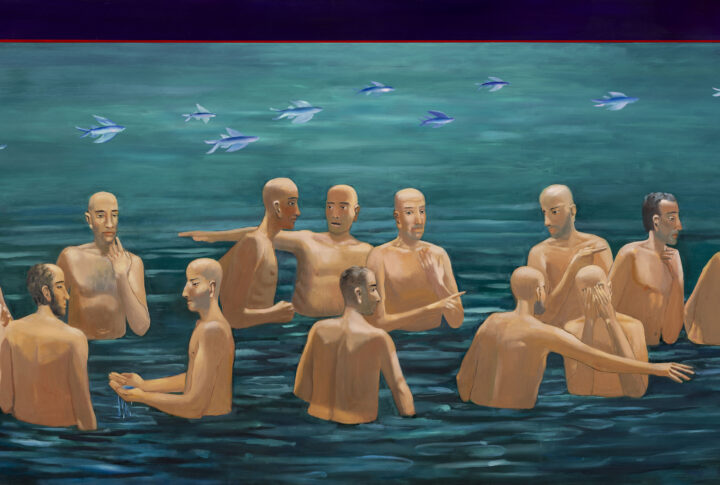

Therefore the exhibition of Džemma Skulme’s works at Daugavpils Mark Rothko Art Center begins with space where the official, doubtful and unofficial (in the Soviet understanding) are located side by side. You can see here

the lyrical and masterful works presenting people’s festivals of the 50-s, the dramatic and even tragic figurative works of the 60-s, the iconic paintings on wood from the first solo exhibition (1968), as well as the officially

commissioned works of the 60-s and 70-s on themes selected by the artist herself as important – Song Festivals and Latvian Riflemen. Just like this – “Latvian Riflemen”, without the insertion of “red” – is how Ojārs Ābols presents the theme in the booklet of Džemma Skulme’s first solo exhibition. Alongside with figurative works which tell about history and war there are intimate, existential nudes which accentuate the dynamics of gestures and body like in a pantomime. Both of the “Tautasdziesmas” (Folk Songs), which have already become Džemma Skulme’s identification signs, are created under the influence of a deep disappointment over the invasion of Prague by the Warsaw pact armed forces. Experiments with cool colors are another challenge of the 60-s. The ideological face of the epoch can be seen in two subject-wise similar but form-wise different paintings under the same title “Ceļamaize” (1967) [Bread to Take With]: the possession of The LSSR Art Foundation (now Artists’ Union of Latvia)

shows that the artist had wished to develop rhythmical forms while the museum has favored genre details. The exhibition also offers to viewers a previously non-exhibited work – a double portrait, which Džemma Skulme has painted after her visit of Paris in 1956 when making a European trip together with Ojārs Ābols. This canvas, done in silvery tones and depicting symbolically joined hands, was rejected by the exhibition of portraits as being

“pornographic”. Such seemingly comical reaction to the refined painting depicting the triumph of love can be explained, because the Helladic impressions of the 19th century symbolist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes or even a resemblance to Francis Picabia’s linear works, or Picasso drawings were not acceptable on the agenda of the progressive Soviet culture.

WHEN THE TEXTURE BECOMES THE CONTENT

The second part of the exhibition is based on the collages to which Džemma Skulme gives different names – “Caryatids”, “Scarecrows”, and “History Notes”, but which are united in their conception – to use everything what can

be found at home. “I wish they were perceived people to develop ideas. Only from what is mine, in my home, what has been accumulated by my grandfather, what my father has stored up and I myself. Only such. Anybody has something of this – just search and find! This is initiated by the Awakening, as naive wish. And also a wonderful joy of a finder about the techniques. All this emerged when you were not allowed to do this, but you did it nevertheless,”7 Džemma Skulme says. The collages have been created simultaneously with the “pure” painting from 1982 to 2012. If their artistic content builds bridges between Latvia and the world, between the Latvian identity scattered across all times and different places, including Skulme’s own individual self, then on the biographical level collages become the author’s bridge linking the Soviet times with independence. A thirty-year-long action during which the texture is legitimized as the content. The scenography of the exhibition emphasizes the transformation of the texture into the content. In the course of time, the form of collages has developed from fragments of different documents and several written phrases up to innumerable

building blocks, where each document, each handwritten text and each field of color apperas with its own space – private, political, historical, abstract – and rams into each other.

These works can be called Džemma Skulme’s neo-cubism, where innumerable virtual spaces have been transformed into a decorative plane. With the image of a caryatid and decorativeness being contact points, the collages in the second space are installed together with the monochrome relief texture paintings of the 70-s which emerged from a drawing, almost a relief, executed in a thick, quickly hardening polyvinyl acetate layer covered over with oil color dissolved in turpentine.

DADAISTIC TURNING POINT

The third space is formed by Models and new works. Džemma Skulme painted the first Models in 2005 – childish, bright colored figures, where she has used childhood drawings of her daughter Marta as a motif. Semantically, the origin of this painting can be related to Skulme’s own nudes of the 1968 – 1969 (Marta draws together with her mother and brother) and to her expressive figurative painting in a wider sense as well. But conceptually they are absolutely different works – executed by Dadaistic techniques as Džemma Skulme’s antithesis of herself. Figures from children’s drawings appear in the picture like ready-made subjects – they are copied preserving the childish dexterity and wrongness.

If Skulme’s nudes of the 60-s defied the power by their open existential position of expressive realism, then the Models and the latest works, where she uses drawings of her own childhood kept by her mother sculptor Marta Liepiņa-Skulme, seem to be defying the heaviness of contemporary interpretation with Dadaistic childishness. Džemma Skulme (1925) still feels dislike to dogmas, and disregards what is generally accepted, thus confirming not only her belonging to avant-garde strategies which determine the contemporary art, but also implementing her individual responsibility and inexhaustible creative talent. The exposition includes works from the collections

of Latvian National Art Museum and Latvian Artists Association as well as from private collections – The Zuzāns family, the collection of Ainārs Gulbis and Guntis Belēvičs, and works and archive materials from Džemma Skulme. The exhibition at Daugavpils Mark Rothko Art Center is organized by the foundation “Mākslai vajag telpu” [Art Needs Space].

Inga Šteimane

1 Skulme, Džemma. Vēriens [Scope]. Recorded by L.

Slava. Literatūra un Māksla, 1983, Sept. 30, pp. 8–9.

2 Here and elsewhere quotations from: Heidegger

Martin. Holzwege. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann,

1980. Translated by R. Kūlis. Riga: Intelekts,

1998, pp. 38–52.

3 Džemma Skulme: Exhibition. Artists House, Riga,

1968. Compiled by O. Ābols. [riga], 1968.

4 Džemma Skulme is head of Latvian Artists Association

from 1982 to 1992.

5 Repše, Gundega. Tuvplani [Foregrounds]: Džemma

Skulme. Riga:Jumprava, 2000, p. 109.

6 The research of Andris Teikmanis on the semiotics

of relationships between art and politics is devoted

to this problem.

7 The recording of the interview on 27/09/2015 in

I. Š. archive.

Varoņi / Heroes. 1969. Audekls, eļļa / Oil on canvas, 160 x 240 cm. Latvijas Nacionālais mākslas muzejs / Latvian National Museum of Art / Tautasdziesma /