Bent Holstein exhibition „FERNWEH”

Bent Holstein exhibition „FERNWEH”

Bent Holstein uses a German word to describe the main drive in his art: Fernweh. The English translation is Wanderlust, but the combination of the two words is a perfect guide to understanding the art of the 73-year old Danish artist. He constantly wants to be somewhere else and his lust to wander into different places is insatiable. These places must have water or mountains and they must have light. Interesting or dramatic light.

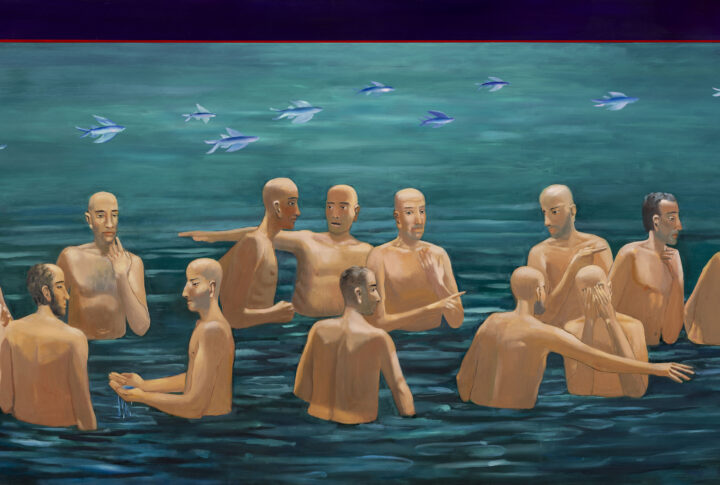

”Why are we always attracted to water? Why do you sail?” he asks and adds ”My art is always coming from somewhere else. My paintings are always painted in my Studio in Copenhagen, but my visions come from The Caribbean, Mexico,. Water is a key element. My best moments are when fishing ”The Flats” in The Florida Keys. The water is a few inches deep. I cannot see the coast. It’s like standing inside a huge soap-bubble. You cannot distinguish water from land – it’s a blurry transition and it fascinates me.” Bent Holstein points at several new paintings, ready for shipment to Latvia and repeats ”They are not naturalistic. I’ll go mad, if I painted nature.”

But he does depict nature. His very own interpretation of natural elements. ”Why does water and mountains fascinate me” he asks and answers his own question immediately ”We Danes are originally lowland farmers. We are strangely attracted to dangerous places like mountains. Both mountains and water demand great respect. There are life-threatening cliffs, ravines, sharks and violent currents. And the difficulties of painting this array of challenges and threats are enormous”.

Today, 50 years after the first public display of his art in Galleri M in Copenhagen, Bent Holstein is still in the middle of a life-long honing of his skills. Technically, he is regarded as one of the most skillful in his generation of graphic artists. He has no formal education in art. He never became an honorary professor at The Royal Academy. He is entirely self-made, autodidact. As Danish Art Critic Peter Michael Hornung wrote: ” An autodidact is a person who has chosen himself as a teacher. In the case of Bent Holstein, that was an excellent choice”. He has constantly been experimenting with new materials, most recently combining painting with photographic images on aluminum.

Bent Holstein is a cityman. He lives in the middle of Copenhagen and has done so his whole life. But basically all his work for more than half a century is based on travels outside his home urban environment. He never sets up his easel and canvas on a beach in Florida or in the mountains of Slovenia, where he practices his overwhelming passion as a fly-fisherman. He doesn’t even bring a sketchbook and pencils. On his travels, his most trusted companions – apart from his Finnish-born wife Mekki – are two permanently watchful eyes and a camera. Having returned to his city apartment and studio, he slowly digests the images in his mind and the photographs and transforms them to the canvas. For a while he even gave up the camera. ”It is the image inside your brain, that counts. Your first impression of what you saw. I paint my impression” he says.

That has been his life since he decided to become a professional artist. The decision was not made when he was a child or a youngster. Art was not a factor in his home or family. He preferred to play music and joined a jazzband. Half a decade later, he told art critic Peter Michael Hornung, that the first time he realised, that a piece of art could be as important and powerful as a piece of music was seeing a painting in a fellow musician’s home. Here, Holstein saw a collection of Danish modern art, particularly members of the COBRA-group of expressionists and especially one picture by world-renowned Danish artist Asger Jorn. The young Holstein did not fall in love with the picture, nor the dramatic and potent expressionism. But it touched him. While visiting Paris in 1960, Holstein saw a painting in an artdealer’s window. So bold and simple, that it almost haunted him afterwards. Just yellow with a black spot. By the Spanish artist Antoni Tapiès. It turned the bass-playing aspiring musician Bent Holstein. Into an aspiring artist. Playing music and painting canvasses was, after all, not his primary job. He was a shipping trainee with the huge Danish shipowner A.P. Moeller-Maersk . That did not last long. He quit after three years and became a full-time artist.

”I guess we had conflicting interests, me and Maersk”, he told me with a typical sarcastic Holstein-smile: ”They were prospecting for oil in The North Sea, I wanted something else. My first exhibition was sold out. I made ten times my monthly salary as a trainee. I realised, I was a painter. Not a shipping trainee”

He became an art critic. He was a popular figure in art programmes on radio and tv. Danish National Broadcasting offered him a job. But a steady job with a pension scheme was not his cup of tea. After a few years, he no longer had to consider another job. In 1982, the newspaper BT listed Holstein as one of only 20 painters in Denmark, who could actually make a living from their art. “You become an artist, because you cannot help it and because it offers you absolute freedom. No one can interfere with the way, you paint”, he said.

Bent Holstein was free to create art and to travel. In his world, the two are intrinsically connected. Travelling in itself holds endless fascination for him. He can emerge himself in travel fables like no one else. In 1992, I interviewed him for at book, published when he turned 50. He talked about British skippers who could find the Caribbean by sailing south from Land’s End with a bowl of butter on the foredeck. When the sun had melted the butter, they made a 90-degree starboard turn and in a few weeks, they hit Barbados. Holstein mentioned how Australian aborigines measured distances in songs and how an eskimo had drawn a detailed and correct map of Hudson Bay from memory, without any knowledge of cartography. Holstein was fascinated. “Only idiots call these people primitive. They just had knowledge…”, he remarked. Movement and art are closely intertwined. When you reach your destination, you find that it is temporary, maybe even disappointing. Holstein mentioned Captain Ahab from Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick”: “He travels endlessly

in his hunt for the Great White Whale. Standing on the deck, where he has drilled a hole for his wooden leg. And when he finally, after a lifelong journey finds Moby Dick, he realises that he had lost interest in it”

A closely related figure in Holstein’s world is the rich man in “The Tales of Hoffman” who collected views. He mobilized hundreds of people and used enormous funds to construct roads and chop down forests so he could reach the spot with the perfect view. He then inhaled the magnificent view and drove away, never to return. The view was imprinted in his memory. That sufficed.

Bent Holstein is a collector and interpreter of views. It was not so dominant in his early works, where he combined reality with abstractions and often animals that logically did not belong. But he took his art a step further. The exhibition Tide Lines at the Asbaek Gallery in 2001 was the turning point. Holstein, the dedicated fisherman, traveller and artist was overwhelmed by the visual drama of the Florida Keys. “Staying in a small hotel in Marathon, in the Middle Keys, I watched in fascination the moving tide, the shifting sky, the change from salmon pink to black, when a storm moves in” he wrote in the exhibition catalogue. He drifts in a boat in search of Tarpon and Bonefish and he steps out of the boat on the flat in knee-deep water “looking around in a circle observing nothing but the silkygrey water and the yellow sky. The tides drawing its lines of debris around your legs in a long drift. The tide lines”

The exhibition got a glowing review from the late Ole Lindbo,e art critic and editor of the Danish Art Magazine:

For many years, the painter Bent Holstein cultivated aesthetic perfection and balance. His canvases were beautiful and controlled , polished and refined. He was an aristocrat among his contemporaries. But the paintings were first of all discreetly adventurous, with an almost hedonistic sensuousness and a refined elegance. In a time when much painting is intended to resemble a tremendous hangover, unshaven and belching, slovenly and wobbling, Holstein became an increasingly solitary figure. With his sensitive sensory apparatus and his special ear for the musical qualities of the color spectrum, he obviously stood out from his surroundings. Like a tapdancer surrounded by stomping hillbillies.”

Ole Lindboe then described Bent Holstein’s new paintings as paintings in which “feeling and sensation were fully unleashed. There were paintings that floated and danced at the same time. There was nature fully orchestrated ,seen and observed with a both sharp and affectionate eye. But there were also paintings full of calm and harmony- and vibrating energy.”

Holstein, on his never-ending search for views, had taken a big risk by developing his art into something quite new and very difficult, Lindboe wrote, but “He reached landwith the entire phenomenon stored in his memory and his retina. And he captured it all upon his canvases. Like a fisherman, he has come ashore with a big catch.”

Sitting in Bent Holstein’s studio upstairs from his apartment in Copenhagen, we go through the paintings, ready to be shipped to Daugavpils for one of the largest ever, exhibition of his works so far. We talk about the pictures, where he mixes photographs and abstract paintstrokes on laminated wood and aluminum. There are broken scenes of dark mountains in Central Europe and a view of a landscape very close to his summer residence by the coast, north of Copenhagen. He is constantly experimenting with new compositions and new materials. It is a never-ending effort towards perfection. I know that he knows, that he never gets there. If he did, like Captain Ahab, he would lose interest. Unlike the rich man in The Tales of Hoffmann his big collection of views are not imprisoned within his brain. They are are constantly being interpreted and transferred into paintings for others to enjoy. And they are all deeply rooted in Holsteins lust to wander and Fernweh.

Lasse Jensen

Lasse Jensen (born 1946) is a prize-winning Danish writer, documentarist and journalist. In his 50- year career he was a war correspondent in Indochina and others wars, USA-correspondent for Danish Broadcasting Corporation and has held executive positions as Chief Editor at Danish Broadcasting and Managing Editor at TV2 News as well as Bureau Chief for Eurovision (EBU) in New York. As founder and owner of Jensen & Kompagni since 1997, he has produced and directed more than 20 documentaries and tv-series. From 2001-2014 he produced, edited and anchored Danish Radio’s media magazine. He has been Associate Professor in Journalism at the University of Southern Denmark and writes a weekly column for the daily “Information”. Danish daily Politiken nick-names him “The Grand Old Man of Danish Journalism”. He is a life-long friend of Bent Holstein. When frequent travels do not prevent it, they lunch together every saturday and have done so for more than 20 years. Lasse Jensen is the author of the 1992 book “From Akwete to Asserbo” about Bent Holstein and his art.