With Gratitude to a New Day. Art historian Inga Bunkše on Basil Alkazzi’s exhibition at the Rothko Musuem

The Rothko Museum’s collection holds works by the artist Basil Alkazzi, created between 2007 and 2024. This body of work encompasses both abstract paintings and visions of vast, boundless landscapes. However, the common thread binding these pieces transcends the mere aesthetic interplay of colour or faithful representations of nature; it is rooted in the pursuit of experiences beyond the visible realm – those that, while not empirically verifiable, present themselves in our surroundings.

Embracing an unfolding journey of spiritual growth and exploration can take one to a clearer understanding of the body as the dwelling place for the spirit – divine energy materialised in a tangible physical form. This naturally paves the way for a reciprocal perspective where physical objects, including hand-cast paper, pigment, and ostensibly mundane motifs, can be infused with spiritual energy (spirituality) as conduits of transcendence.

The earliest works in the collection are from Alkazzi’s “Odyssey of Dreams” series (2007). According to the American art critic Donald Kuspit, a commentator on the artist’s oeuvre, these drawings emerged at the culmination of Alkazzi’s spiritual journey – a personal odyssey “related to the person’s efforts to break out of the standard ego-bounded identity” or, as Jung puts it, “a journey from ego to self, a journey of self-realisation”. [1]

The foundational material of these works – hand-cast paper, consistent across all of Alkazzi’s creations – is unevenly toned with heavenly blue, conjuring the impression of an infinite body of water. White waves crest gracefully across the surface, subtly morphing into bird silhouettes soaring at the composition’s upper edges. Engaging with these pieces invokes the “oceanic feeling” the French poet and mystic Romain Rolland articulated in a 1927 letter to Sigmund Freud, describing the boundless “eternity” of emotional experience. Drawing inspiration from Ramakrishna’s teachings, Rolland perceived this as a universal emotion accessible to individuals of all faiths. [2]

Freud acknowledged the phenomenon referred to as the “oceanic feeling”, attributing it to a remnant of early childhood experience – specifically, the “primary ego feeling” of an infant prior to developing self-awareness, a deep-seated feeling of being inseparably connected with the outside world as a whole. [3] Alkazzi’s oeuvre vividly reflects this sensation of indivisible unity and a pre-ambivalent state of wholeness. The concept of “prima materia”, or the essential substance of creation, emerges solely to the perspective of a bird (symbolising the Divine Spirit), thus maintaining its ineffable mystique and evading rigid formal categorisation. This inherent mysticism compels one to pursue meaning that transcends the individual as the focal point of the observable universe.

Alkazzi’s surreal abstract compositions frequently revolve around a single motif – an abstract floral form. In the “Twilight of Whispering Dreams III”, a slender pistil reaches upwards, expressing an instinctive and confident yearning for fertilisation. Within Alkazzi’s oeuvre, the act of conception is a spiritual phenomenon akin to the Annunciation, wherein the angel Gabriel tells the Virgin Mary of her divine gestation. The artist materialises the presence of the Divine (the Holy Trinity) through the luminous tripartite shape at the flower’s apex. As noted by Donald Kuspit, “The Annunciation suggests that all sexual acts are implicitly – potentially – spiritual, and all spiritual acts, including making art (certainly religious icons), are implicitly sexual.” [4]

Another vision of immaculate conception is evoked in “Beatitude in Anticipation III”, wherein a flower unfurls beneath falling stars, reminiscent of Danaë receiving Zeus, descending upon her in a golden rain.

Observing the interplay between the dazzling yellow light penetrating the violet hues, one may ponder whether the viewer perceives the sensual confluence and transference of energy. In “Transmigration II”, the artist conveys both a sexual embrace and a moment of spiritual revelation through the contrasting colours, depicting a fleeting instance of unity with the primordial whole. The outcome is radiant and ecstatic – yet always mediated by human perception, standing between the subject and the Absolute. This, nonetheless, does not diminish the impression that Alkazzi has bestowed upon the viewer a transcendental insight – akin to the human experience of communion with the Divine through the life and death of Christ, as suggested by the symbolic use of purple, the colour of Christ’s Passion.

A peculiar mysticism lingers in the speckles diffused across the upper sections of Alkazzi’s works (particularly in the “Twilight of Whispering Dreams III” and “Beatitude in Anticipation III”). These recall manna, the miraculous nourishment bestowed upon the Israelites from the heavens. In ancient philosophical discourse and early Christian texts, manna is frequently linked to the Logos – a creative force mediating between the Divine and the mortal world, an essence palpable in Alkazzi’s oeuvre.

In “Birth”, one can discern an abstract depiction of a flower. At its core, the pistil – or the new Creation – bursts forth in a flash of fireworks, propelling itself into the world. In this moment of emergence, it severs its connection to the primordial “ocean”, the amniotic fluid, to draw its first independent breath. Within this nascent creation (the artwork itself), the full force of its two Creators – the Earth and Heavens – is gathered and brought into being.

The moment of birth is a recurring theme in Alkazzi’s oeuvre, manifested in numerous variations across the entire spectrum of creation, from physical delivery of a new life into the world to artistic genesis, on which Donald Kuspit remarks that “self-love and self-reflection are enough to make one creative.” [5]

At times, Alkazzi depicts seemingly modest landscapes, elevating them through his reverence for nature as the dwelling of the Divine. Works such as “Tuscan Landscape” and the “Winter Landscape” series show restless washes of colour and undulating mountain silhouettes, which rise and fall like rolling crests. Yet, somehow, these folds and furrows convey a soft tranquillity and enlightenment, affirming the presence of eternity – a vital notion in an era where what was once considered permanent can crumble into ashes in mere hours or likely even minutes. That said, Alkazzi’s landscapes are also deeply sensual, suggesting that sexuality can be framed as a transcendental experience. This is perhaps best seen in the sensuous “Tuscan Landscape” and the symbolic fertilising communion between earth and sky in “And Still This Green & Pleasant Land II”.

The notion of timelessness is also evident in the series titled “A Setting Sun’s Lingering Farewell Kiss”, wherein two intertwined trees embrace as they welcome the night. Their statuesque presence embodies self-sufficiency, strengthened by their kiss – a breath of the soul, offering renewal and vitality. Like the cyclic rhythms of the sun’s setting and rising or the annual resurgence of blooms in deciduous trees, the spirit persists; life merely transitions through various forms.

To conclude this brief tour of the artworks, I return to the profound sense of the “oceanic feeling”, an overwhelming sensation born from observing the artist’s “Sunset”, “Another Day, Another Dream, Come”, and the most recent “Summer Sunrise” series.

The vastness of the waters (or perhaps a shadowed landscape darkened by the setting sun) situates the viewer in the imagined centre of an infinite ocean, invoking a sense of the Sublime. This sensation recalls the awe experienced when contemplating the grandeur of nature in Caspar David Friedrich’s landscapes. As Georges Bataille [6] noted, an infinite void, devoid of inherent meaning, grants humanity the space to construct its world, imbuing it with whatever significance it chooses. In gratitude for this potentiality, every new day – though manifestly cyclical and therefore seemingly eternal – deserves our reverence and celebration.

Inga Bunkše, Mg. art.

Translated from Latvian by Irina Presņakova

[1] Donald Kuspit, Basil Alkazzi – An Odyssey of Dreams, A Decade of Paintings 2003–2012. From: https://www.basilalkazzi.com/page/publications/an_odyessey_of_dreams.html

[2] William B. Parsons. The Enigma of the Oceanic Feeling. Revisioning the Psychoanalytic Theory of Mysticism, Oxford University Press, 1999. page 114.

[3] Zigmunds Freids. Īgnums kultūrā [Sigmund Freud. Civilization and Its Discontents]. [Translation from German into Latvian with commentary and postscript by the translator Igors Šuvajevs].

Sigmund Freud 1856–1939. 2000

[4] Donald Kuspit. Basil Alkazzi – An Odyssey of Dreams, A Decade of Paintings 2003–2012. From: https://www.basilalkazzi.com/page/publications/an_odyessey_of_dreams.html

[5] Ibid

[6] George Bataille. Theory of Religion. New York, NY: Zone Books. 1989.

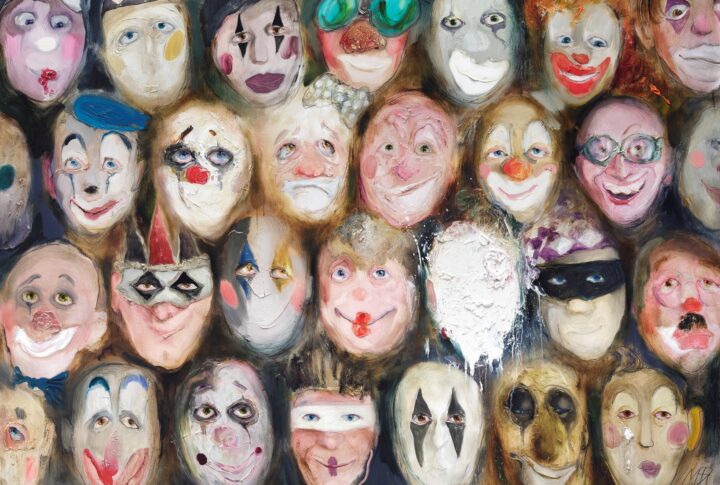

Basil Alkazzi. Odyssey of Dreams IV, 2007. Gouache on paper. 46 x 31 cm. Inventory number GL-587.