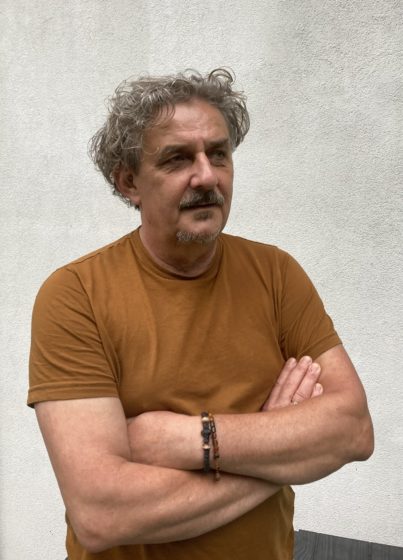

Hallway talks with Jarosław Perszko (Poland)

Rothko Centre: The most memorable periods in your creative career – what are they?

Jarosław Perszko: Certainly, the very beginning when I embraced large scale objects, which usually work in a public space. I made a seven-meter-tall sculpture, a column which is located in Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń (my Alma Mater) Library courtyard and seems to be propping up the sky. I understood right away that plain figurative thinking was not enough to me, that I need to think spatially, beyond the object – what’s beside it and how it interacts with the environment – to notice how the two correspond.

There has also been a pretty odd period of time in my life, when I didn’t create art at all for about ten years. My work then had nothing to do with creativity – I was just casting other artists’ pieces in my own moulding workshop. Seems peculiar, but definitely it was not a waste of time. Then it picked up again and, bit by bit, I was coming back and felt the need to speak out again. For quite some time, I thought I had nothing to express and art felt hollow and void. Then, after a decade of silence, I slowly returned to exhibiting. I was lucky – people still remembered me, because usually, when you disappear for ten years, you’re almost forgotten. At that time I was built different than before and I grew up enough to tell on my own.

RC: Why installation art?

JP: Because there’s so little emotion in (purely) figurative art to me. I want to explore art and sculpture in particular as a medium and share my insights with the viewer. Not only do I want to stimulate the viewer’s senses, but to connect them with the surroundings as well. I want the viewer to feel immersed in art head to toe.

RC: The Rothko Centre art space, Mark Rothko’s persona and artistic ideas… Do they help you with your creativity?

JP: You know, I still haven’t cracked the Rothko phenomenon, his genius is so elusive, difficult to comprehend, maybe even overwhelming. It’s difficult to live up to this place and its standard. This fear can be shattering.

RC: You mean it’s a load of responsibility?

JP: It is a huge one. But I am who I am – if I claim I don’t know something – I mean it. I’m not trying to cheat or force myself to understand. I try to use some of Rothko’s elements: the presence of light in a painting, its aura or spirit. As for the form of creation, my work is completely different. There are only a few twentieth-century artists with such a profound impact on the audience, artists who touch our very core.

It’s in human nature – we long to be touched deep inside by some kind of higher matter and these touches, these attempts at conversation, make up a transcendental experience. Rothko managed to connect with the unreachable – what we find difficult to touch and put into words, he somehow sensed it. I think that is something Rothko and I might have in common – I try to operate formal solutions which are ‘easy’ to perceive by a viewer, meaning they don’t demand understanding or knowledge. The only demand is to be open to a sensory experience here and now.

RC: Now you’re installing your latest piece at the Rothko Centre. Is it an unpredictable process?

JP: I’m not sure, I haven’t seen how it works yet, but I feel and expect things to turn out just fine.

I enjoy the unknown – it keeps me creative and provokes exploration. Otherwise, I get bored. I’d rather take a walk or go mushroom picking than do the things I don’t really get. It’s like being on the road without knowing where it will lead you, but you just keep driving.

My idea of the exhibition “Titans dancing” presented in this venue was to create a spatial display which would allow one to perceive a light as a physical matter, to create a similar emotional state as a viewer would recognise aesthetically experiencing Rothko’s paintings. I’d like viewers to notice a processuality of Rothko’s works the same way I do, and I wanted to achieve it without any literal references in formal creative solutions. My installation is something more than only a display of luminescent neon bars.

RC: Then, any result, whatever it may be, can be ‘done up’ with a concept that goes with it?

JP: No, not really. If you fail, just embrace it, be humble and say “not this time”. You need to face it – you’ve lost. We all have our ups and downs but still, more or less, we know what to do, like carrying out certain actions to reach the goal, even if there’s no sense of direction. When you have the knowledge and a natural skill, you also have a feeling where to aim.

RC: What kind of feedback do you expect from your viewer?

JP: I don’t mean to shock or provoke, I prefer to create a profound experience. Of course, someone may think: what’s the big deal? and simply walk by, but open, perceptive and sensitive viewers will be contended.

RC: Does the time affect the viewer?

JP: I think time changes people but not at their base. Feelings, in their primary nature, get triggered regardless of one’s knowledge, they come from openness and perceptiveness. Sometimes we (consciously or subconsciously) lose our emotionality or cut our feelings away because we think it will toughen us up. However, if we hold on to our sensibility, the fundamental role of art remains the same – to impress and to touch. That causes a reflection on the kind of imprint art has made on the soul. After this moment of resonance, certain thoughts and analysis occur – why things happened this way and not another… and the conclusion can take your breath away, you find yourself taking a deep dive into what is beyond any words of description.

RC: What’s your way out of the void?

JP: I think about art in terms of religion – whether you feel it spiritually or not, I treat it with profound respect. After all, art is so diverse – there is also the kind that sparks joy and entertains but I do nothing of that sort. If I have nothing to express, I don’t create and I don’t exhibit. So the stillness in the creative process I once found so overwhelming can be a blessing too, a purifying experience.

RC: Tell us about your work in the context of the “New Spirituality” group show.

JP: In a way, it’s related to what I usually perform, to my very personal and private work. As I mentioned before, the title of my piece is “Titans Dancing”, which is obviously inspired by Greek mythology, where titans – gigantic gods, represented destructive forces. In my piece, I perversely pictured them with a very fragile medium – neon bars, which seem to be representing only skeletons so easy to be damaged. I purposely refer to the cradle of European culture and philosophy, because I feel our society somehow moves away from its values that, we believe, had grounded humanity and certainly were shaping it for centuries. On the other hand, people had to face some kind of dualism in thought or ideas and acts since forever – what is good and what is bad (to simplify the most). I don’t feel I’m in any position to judge the modern society and I don’t know if I’ll manage to spark any thought of some universal concerns, but if through my work I’ll be able to pause someone for a couple of minutes to reconsider something that really matters to him/her, I’ll be more than happy.

RC: In what ways do you find you’ve changed over time?

JP: I’ve changed everything in my work, but at the same time I’ve changed myself. Looking at my creation throughout all those years, it can be easily noticed I’ve always been into “novelty”. I’ve always looked for new means to express issues bothering me at a given time. I’ve worked with sand or light drawing, now I do neon installations and I’m still excited. I keep finding new things. I want to keep working on it, to experience it. Perhaps one day my concept will change and I’ll focus on something else or maybe I won’t do anything at all. To me, creating objects just for the sake of doing them is meaningless. The world is littered with pseudo-art and I’d prefer not to be a part of this wrong phenomenon. Some time ago, I organised a symposium which had been carried out annually for four years with various artists invited to participate. They came over and their main task was not to create art, but to share thoughts and ideas. We did this with a friend of mine, a French artist Patrick Bailly-Cowell. So, we went for the debatable format of the event with sharing experiences and stories among our befriended artists, bringing them together to put forward ideas and suggestions. Largely, artists work to feed their own egos.

RC: Is that a bad thing?

JP: Overall, artists are sick; I’m not fond of them. I know it sounds harsh, but unfortunately usually I’m not proud of this community which makes me feel split a bit as I’m a part of it myself.

RC: Why so?

JP: I find it too haughty, too needy, too demanding.

RC: And you’re different?

JP: I hope I am. I manage on my own, I don’t ask for anything.

RC: So, you’re a loner?

JP: I’d like to paraphrase Vysotsky: notes prefer to dance solo…

RC: So, you think your work wouldn’t fit with the current group show context?

JP: No, it wouldn’t. I would outshine them all (laughs).

RC: Why did you become an artist and not, let’s say, a physicist or mathematician? After all, your material is more to do with exact sciences and the world of technology.

JP: Fun fact – I graduated high school from a physics and mathematics major (laughs). Actually, I come from a family of foresters and maybe I should have become one too (laughs hard). To be honest, logical thinking plays a massive part in art as it embodies an actual image of reality, something that’s taken directly from life. As an artist recreates elements of reality, for something to become a principally new element, it needs to have internal logic and function as an organism. I mean, if you want the new feature to become a permanent fixture in our reality. This is why I mentioned heaps of rubbish that shouldn’t even be here. If something exists, it must be meaningful. And there can never be too much of that.

RC: Why do you think we have such an overabundance of artists?

JP: That’s a problem because I see artists as a destructive force that will ruin our world. We have so many artists, but what can you do? Time will tell what is true art and what is not.

RC: Do you share your secrets with your students? I mean, you are a professor.

JP: I try my best to be a supportive tutor, especially when I see potential in a certain piece of work. I try to share as much as I can, considering my heart, all my knowledge and experience.

RC: And still – what is art and what is not?

JP: A major question underlies my definition of art – am I moved by it? Does it speak to me and catch my eye? We are so overstimulated by new images it’s difficult to recognise the actual quality among them. Some things hit us and hurt – that’s one of the basic features to catch my attention.

RC: Name something that speaks to you as a statement or a philosophy.

JP: Hemingway has said: true greatness is not where and who you are, but in what you do. I totally agree.