The Inward Gaze: a Conversation with Kang Haitao

The Inward Gaze: a Conversation with Kang Haitao with Enrica Costamagna and Philip Dodd

Our conversation with Kang Haitao moved from Buddhism to existentialism, from the artists Feng Zikai and Giacometti to his own life in provincial China. It is out of such a rich mulch that Kang Haitao has cultivated a profoundly spiritual art.

In the West, twenty or thirty years ago, when materialist explanations of art were rife, it was not always easy to talk about spirituality. Things have changed. In Western scholarship, a sign of the times is Charlene Spretnak’s The Spiritual Dynamic in Modern Art (2014); and in recent exhibition history, the most telling evidence is the 2019 Guggenheim show of the theosophist abstractionist Hilma Af Klint, which is the most popular exhibition in the history of the museum.

In this context, this exhibition of Kang Haitao is timely. Spirituality, simplicity, inwardness and nature are amongst the imperatives of our times – and also of Kang Haitao’s own work. He was born in 1976 to teacher-parents in a village outside the south-western city of Chongqing which became in the Second World War the capital of nationalist China. Kang Haitao’s year of birth was also the year of Mao Zedong’s death and only two years before China’s opening up, both economically and culturally. Between 1978 and 1987, it is estimated that over 5000 works in the fields of Western philosophy and thought were translated into Chinese, ten times more than in the previous thirty years.

An older generation of artists often had to experience Western art through books which contained only black and white images. But belonging to a younger generation, Kang Haitao remembers that he did have access to artbooks with coloured images — ‘in the first or second year of high school, one of my teachers showed me a book with works by Renaissance masters, such as Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael’. The teacher wanted his students not to paint or draw from life but to learn by imitating past masters. Kang Haitao was impressed with both their technical mastery and the level of detail in their paintings — so unlike the art traditional in China, he thought.

After leaving school, Kang Haitao enrolled as a student in one of the most famous art schools in China, the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute (SFAI). In the years following Mao’s death, when Kang Haitao was a child, the Academy had been a fulcrum of Scar painting and rustic realism; and it produced many of China’s famous contemporary painters who were engaged with China’s recent history, such as Zhang Xiaogang(1).

Kang Haitao took a different road — a singular one. He says that he never set out to be a ‘contemporary Chinese artist’. Such artists often had political interests and, as he told us, ‘I am not sensitive to politics’ — what has compelled him, as he put it, is everyday life and simplicity as routes to spirituality. His art has clearly found an echo in the wider world, and he has been shown in major museums in China, is collected by important public and private museums, has sold well at auctions and exhibited widely in the West.

This is his first major solo show outside China, and after the Mark Rothko Art Centre, it moves to London. The question for those encountering Kang Haitao for the first time, without knowledge of Chinese culture, is — how do we experience and understand these paintings? As the German-English painter Frank Auerbach says, ‘painting is a cultured activity — it’s not like spitting, one can’t kid oneself’ — nor, one should add, is looking at painting a natural activity.

The title of this exhibition, Tender is the Night: The Art of Kang Haitao, is a phrase taken from the poem ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ by the English poet John Keats (and later borrowed as the title to one of his novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald). In Keats’ poem, there is an unbearable and irresolvable tension between daily life where ‘but to think is to be full of sorrow’ and the night-time song of ‘the immortal bird’, the nightingale, which gestures towards a life beyond suffering and beyond death.

There is a tension, too, at the heart of Kang Haitao’s work — a yearning for a world beyond the everyday one, but, paradoxically, the lexicon used to explore this spiritual world is largely in his earlier paintings the world of everyday provincial life: old factories, old schools, walls, isolated trees. More recently, the lexicon of the paintings has shifted, and there is now a complex interplay between inner and outer, between light and shadow, substance and reflection (see ‘Memory of Light’), and the colour palette is higher.

Covid meant we could not travel to Beijing to conduct the interview (although we have met Kang Haitao there several times), so we talked by WeChat — and began by asking him why so many of his works are ‘night paintings’.

KH I think that life, the condition of life, is or rather should be, like walking through the darkness of the night. When you are walking in the deepness of a dark night, you have to — you can only — walk forward. You can’t see anything. You have no distractions. You can only follow the direction you are going in. During the day, of course, you can choose to follow different paths, you can be distracted by things around you. I think life should be like night walking. We should be inward-looking, focused on our inward condition, not distracted by outward things. The world outside is full of temptations, materialistic temptations that distract us — analogous to walking during the day. Live life as if walking at night.

EC/PD Your whole ‘inner world’ practice is a negation of the outward facing world, where everything is a financial transaction and where everything is reduced to a matter of consumption. Inner and outer; night and day; substance and shadow — your paintings explore these tensions with what we might call hallucinatory intensity — you yourself have said that there are ‘no longer any sober observers at the moment(2). To make your art, have you found resources in the history of Chinese art?

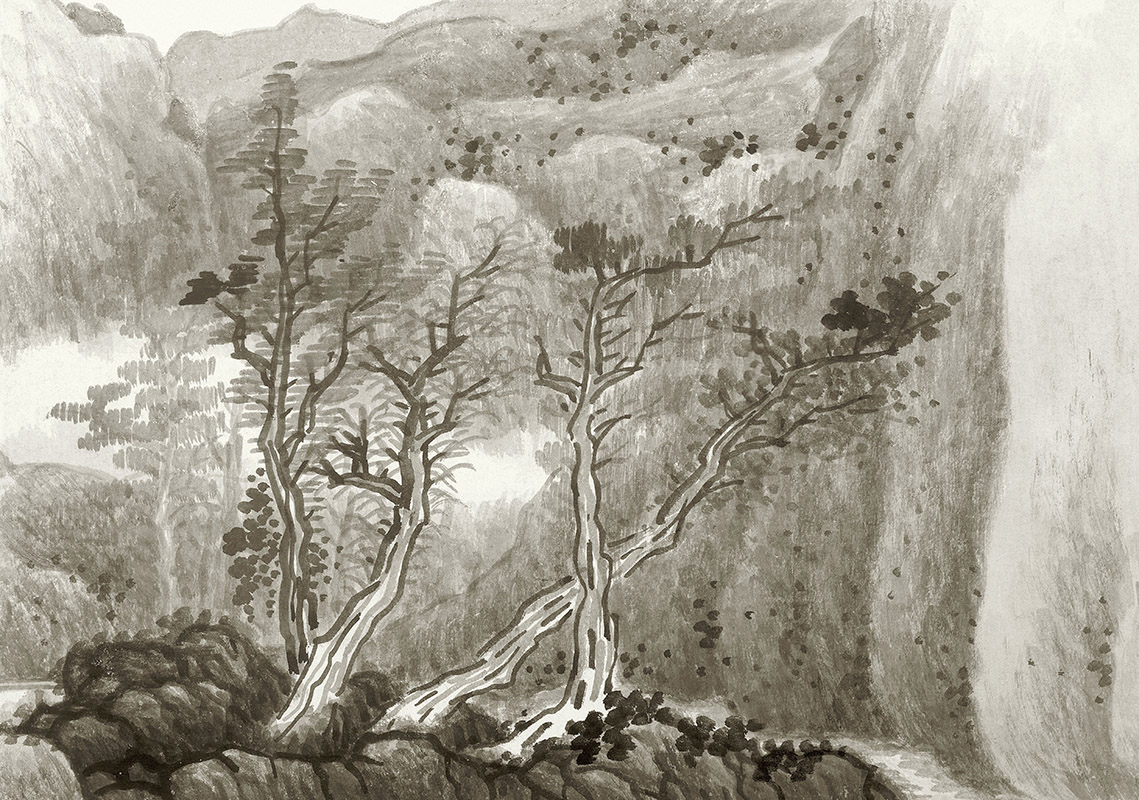

KH Yes, I am a great admirer of Gong Xian (1618—1689), who at first sight might seem to be simply a landscape painter, but he is not. Nor am I. For me, an isolated house, a tree, a wall, anything from quotidian life can be a subject if it moves me.

Gong Xian (Qing dynasty, 1618–1689): Landscape (detail), 1679. Hand scroll, ink on paper, 30 x 997 cm.

Tianjin Peoples Fine Arts Publishing House Co., Ltd, Tianjin, China

In one sense, Gong Xian is a very different artist from me because he is always explicitly reaching out to a dimension that is beyond us. I am rooted in everyday life. What I connect with is his style, his remarkable jimo (積墨) [a way of using ink that layers it rather than splashes it].

With oil, the colour black is just black; jimo will allow an artist to produce different layers of black — it’s all about the light that comes through. It enables you to show all its nuances. It’s really the light through the darkness that matters. I have tried to achieve this in my own work by using acrylic, which like ink, can be laid down quickly. I use jimo, especially when I want to represent the night or woods. In Chinese, we would say 深而不堵, which means ‘deep darkness but not absolute’. There is always the possibility for light to cut through.

EC/PD As we look at your work, it seems to us that you are loyal as well to what we would call the Buddhist principle of ‘less is more’ — which is both an ethical and aesthetic position.

KH That’s certainly true, which partly explains my admiration for another artist — Feng Zikai (1898—1975). Again, a very different painter from me but I share with him a passion for everyday life and for the simplest of means. Like Feng Zikai, I am looking for the spiritual in everyday life. Nature, the simple life — that is what connects me to Feng Zikai or, for that matter, to Giorgio Morandi. Both artists led a simple life — and their art exhibits an extraordinarily hard-won simplicity. They act as if ‘less is more’ — to use a phrase from Buddhism — and that’s what I share with them.

Feng Zikai (1898–1975): Reading by the Window near a Pine Tree. Undated. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Framed hanging scroll; ink and color on paper. Image: 48.3 × 33 cm. Bequest of Robert H. Ellsworth, 2014 (2019.290.11). © 2022. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence

EC/PD Are there other Western artists who have mattered to you?

KH Yes, Western artists and writers. I remember reading the French writer Maurice Blanchot [an existentialist who wrote well about the mystery of life — he was raised a Catholic] who once wrote that true freedom can only really be achieved through solitude — that’s when you are truly yourself. That’s our existential condition. Blanchot also wrote well about the great artist Alberto Giacometti. Giacometti felt that solitude or loneliness was less a feeling than a condition of life. That makes sense to me. He once wrote that he was as lonely as a dog. Giacometti’s journey to existentialism is not dissimilar from that told in Buddhism — or Hinduism for that matter3. All of them are looking to make sense of the mystery of life [in Chinese, the word 神秘 means both ‘mysterious’ and ‘mystical’].

Giacometti, Alberto (1901–1966): Dog, 1951 (cast 1957). New York, Digitale (1)(A) Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Bronze, 45.7 x 99 x 15.5 cm. A. Conger Goodyear Fund. Acc. no.: 120.1958. © 2022. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

This encounter with Kang Haitao disrupts the received Western view of what Chinese contemporary art is — either explicitly politically engaged or calligraphic. Kang Haitao belongs to what in China is called the 70s art generation, neither forged in the heat of the Cultural Revolution nor simply at ease in a globalised China as are later generations.

It is Kang Haitao’s ‘principled unease’ that distinguishes him: to quote Keats’ ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ again, these are paintings where ‘the heart aches’.

OLD HOUSE

This work is actually a commemoration of my old college campus. I spent lots of happy moments there. Much later, I learnt that a dilapidated dorm building on the campus was going to be destroyed. So I took many photographs, went back to the studio, put them on the floor — but deliberately messed them up. It’s not a realistic painting, neither am I much interested in purely realistic works. My work is not nostalgic; even when I look at scenes that might be related to my past. I want to find the spirituality that shines through such things. I am not looking backwards. I look forwards.

NOCTURNE

For me, this painting is unusual — I painted it in one session. It is a window and what interested me was the frame that divides the indoor and outdoor space. I like the relationship between the glass and the trees that are outside, and the way the light and shadow play with one another. For me, the interplay between the window and what is beyond it is an expression of the relationship between my inner self and the outer world. That’s what captured my imagination.

HALF SHADOW

For some time, I have been fascinated by the fact that light and shadow play with one another. One day, a long time ago, I took a photograph of a wall and I saw a shadow projected directly on the wall decorated with white mosaic tiles. A very clear image, a very distinctive shadow with a geometric contour – and I was fascinated because of the immediate feeling that there was nothing between me and the wall. That there was nothing in between fascinated me.

(1) Gao Minglu, Total Modernity and the Avant-garde in Twentieth-century Chinese Art, MIT 2011, p 128.

(2) Fan Zhiling, Memory of Light. Kang Haitao’s Landscape Painting

(3) Stephen Batchelor, Alone with Others. An Existential Approach to Buddhism, Grove Press, 1983

Enrica Costamagna has worked in galleries in Berlin and London, lived and worked in China and co-curated exhibitions in several Chinese museums. Her writings include a recently published essay in Zhuangshi, China’s most influential design magazine. She speaks fluent Mandarin and four other languages and is co-director of the cultural agency Made in China (UK) Ltd.

Philip Dodd, former director of London’s ICA, has curated exhibitions in Beijing, New York, London, Moscow and Singapore with artists as various as Sean Scully and Yoko Ono. Named one of the world’s 100 Top Art Innovators by the American magazine Art&Auction, he has published numerous books on art, film and literature and produced films with the artists Steve McQueen and Damien Hirst as well as with the late Palestinian intellectual Edward Said. He is the chairman of Made in China (UK) Ltd. and he has been named as one of the curators for this year’s Guangzhou Triennial.