CONTROLLED FLIGHT OF FREE THOUGHT

Mārīte Kluša

Interior designer and graphic artist Mārīte Kluša was born in Pļaviņas in 1951. Her mother Jadviga Kluša was a talented craftswoman and recipient of the honorary title ‘People’s Master of Applied Arts’. Mārīte Kluša graduated from the Department of Interior Design at the State Art Academy of Latvia. For her graduation project, produced under the tutelage of Voldemārs Šusts, she designed an adaptable system of visual propaganda for a manufacturing plant. Her career as a designer took her to several enterprises, including the Construction Department of the Locomotive Repair Plant in Daugavpils (1975-1976). The artist has been based in Ventspils since 1981. Her field of interest covers interior design, applied graphics and graphic art. She began exhibiting in 1975. In the early 1990s, Maija Galdiņa described Kluša’s creative output as “delicate, featherlike drawings that add a romantic flair to mundane motifs and elements of the natural world”.

Mārīte Kluša attacks

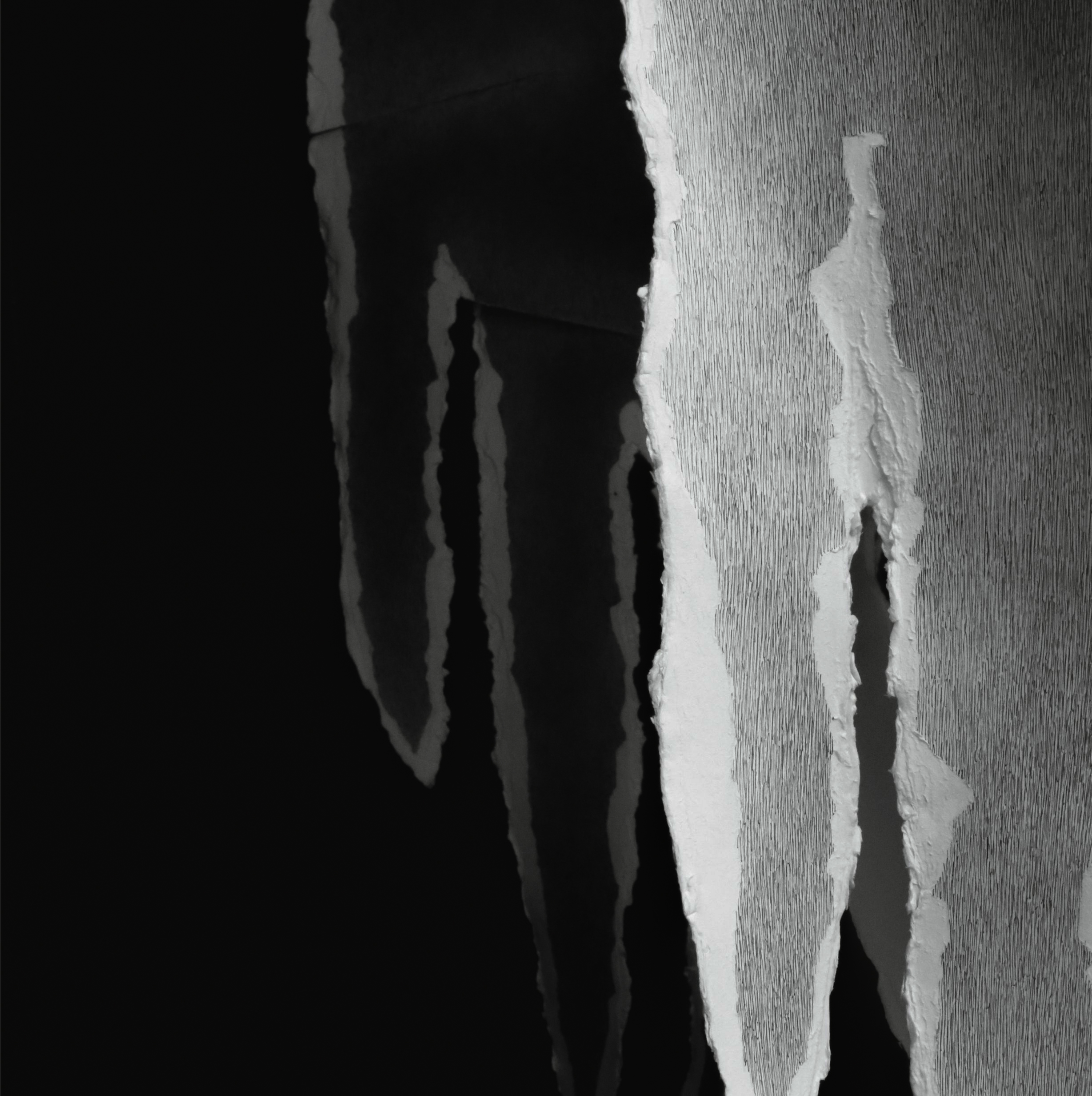

Kluša’s creativity is not limited to two-dimensional work. The artist’s latest creations add a new dimension to her beloved motif of graphite netting spilling over the edges of a sheet of paper. Post-2016, her creative pursuits have taken a new and significant turn. No wonder the two working titles for this exhibition, Freedom is a Conscious Need or Controlled Flight of a Free Thought, seem to imply both the randomness often associated with tearing paper and the artist’s conscious (controlled) action. Kluša’s graphic works are three-dimensional objects brimming with drawings that remain the artist’s signature art form.

The exhibited works from the Simbiosis series (2016-2017) are abstract messages cut short by the passage of time and stripped of their addressee. The densely shaped (moulded) paper, the bilateral dimensionality of which is enhanced by shadings in graphite or ink, should be examined from both sides. With its irregular surface speckled with deliberate extractions, the paper plain reminds the viewer of the chance technique discovered by Milanese painter Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), which in the years to come would intrigue the Italian art group Gruppo Origine (1951). Another obvious reference is Cesare Peverelli. Fontana cut his monochrome works with a razor or a cutter, declaring: “I don’t want to make a painting, I want to embrace the universe, to give art a new dimension and link it to outer space, the infinity of which extends beyond the flat picture plane.”

“I have always wanted to work with abstraction. The value of abstract art is that every artist can find something of their own in it. I couldn’t find anything, and I’d begun to think that I never would. As Andy Warhol once said, you should make what you love above everything else. Well, he made money… But I can work with wet paper, a skill I acquired from my early experience with Soviet design, and I love doing it. I can stretch it, shape it, paste it and so on,” says artist Mārīte Kluša.

The dense shading of ink or graphite, reminiscent of heavy rain, no longer lifts from the sheet of paper the familiar, natural motifs that used to be the hallmarks of Kluša’s creativity in its earlier periods.

Unlike the expressive landscapes, macro flowers, and even portraits, all of which have remained in the past within the limits of the paper plane, these shadings outline what could probably best be described as imprints of the images captured, almost like on a basic camera, by our inner vision.

Through experiments with paper, glue and ink, the artist has arrived at emotionally impressive objects which, seen together, seem to give an impression of an attack. Preparing this one-work exhibition (Résumé) took the artist more than a year. Here is how Kluša describes the technical side of the process: “For me, manipulating a surface is a time-consuming process, because the depth and smoothness achieved with a drawing must be combined with an almost out-of-control shape derived from the tearing of paper. In addition, the glued sheet of paper resists shaping, and different varieties of paper behave differently. In this work (Résumé), I used almost my entire repertoire of techniques that I had found in my previous experiments – it is indeed a résumé, also in the technical sense.” The artist claims she has always wanted to create a piece that would involve masses of people, and she quotes the influence of fibre artist Magdalena Abakanowicz.

Résumé (2018-2020) also works in the context of global events – the isolation brought on by the pandemic, the fear of interaction and the longing for human contact reinforce the artistic impact of the piece. The circumstances of exhibiting the Résumé at the Intro Hall of Ventspils Theatre House were no less peculiar – the small room filled with floating, weightless, ghostly, most likely humanoid silhouettes was shrouded in mist, which was almost real. The graphical creatures faded and vanished, almost like participants of an uncanny yet picturesque performance, and every visitor became an unwitting contributor to the exhibition, organically draw into the company of its eleven images.

From the artist’s standpoint: “These images are people with their own individual wounds that they end up nursing throughout their lives. The piece also echoes the context of global events – we clearly see how civilisation is destroying itself from the inside. A wounded person is always a tragedy. And the apex of art certainly is tragedy. But I’m not going to pursue this topic any further.”

An artist who creates a new piece in deliberate dissonance with her tried and tested techniques is no unprecedented phenomenon. And yet, when a seasoned graphic artist attacks paper, setting scores with its uniformity, bending it to her artistic will and producing a three-dimensional abstraction from a two-dimensional plane, it is a sign of artistic maturity, courage and strength. For attacking yourself is the hardest.

Ieva Rupenheite